My dream life is so lush I look forward to going to sleep. Realizing the stuff of dreams arises from waking life, I tend to steer clear of media that churns audiences into a permanent state of post-9/11 panic. I would rather watch paint dry on an HGTV Macmansion.

Imagine my dilemma at being swept up one night in the harsh reality of an Independent Lens film about undocumented immigrants. Within minutes of watching East of Salinas on PBS, I identified with Oscar Ramos, a Salinas, California elementary school teacher, and I ached for Jose Ansalda, his young student followed by the camera for three years as his migrant worker parents struggled to keep him safe from gang violence and keep his tummy full enough not to cramp or growl all morning in his classroom. On days when nothing but milk was in Ansalda refrigerator, they failed in that department, and Jose fretted his way to school lunch.

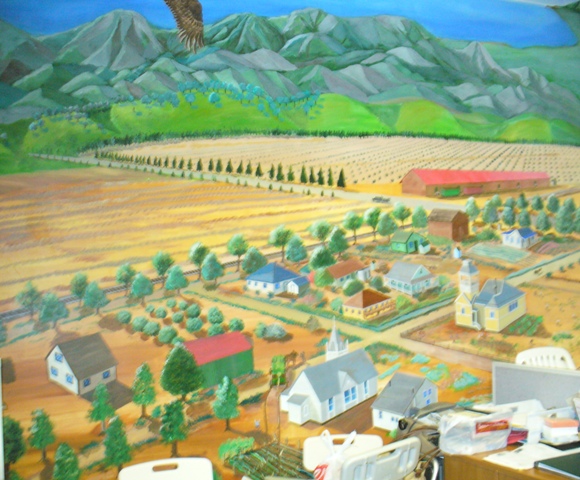

Their story haunted my dreams, drifting into Salinas lettuce fields where Jose's asthmatic mother labored within a mist of pesticide. She bent low with a sharp knife to lop off lettuce head after lettuce head grown in seemingly infinite rows, tossing the lettuce onto a conveyor belt, all but her face covered to ward off the scorching sun. And that was on a good day, when she managed to work and feed her children!

I returned in dreams to the cramped, sparsely furnished apartment where Jose' little sister sat, perseverating to and fro on a loveseat, her body attesting to the family's excruciating tension, TV cartoons her mode of escape. I saw how Jose attacks his math homework, reveling in the conquest of solvable problems. Proving he is smart and tenacious, and despite his status as Mexican born and lacking documentation to stay in the United States, picturing math leading him to a college education. Just as Oscar said he had aspired and entered University of California Berkley, given a bygone era when such students were ultimately welcomed.

Oscar is my idea of a dreamy man, wielding his success to lift up the children in his care, introducing them to the larger world - such as the Pacific Ocean 20 miles from Salinas. And leading them to experience wonder in the classroom and in field trips. Oscar does not abandon children. He see their wounds and does not turn away.

What to do with these wounds? I can tell you and anyone who wanders to this site: Dare to watch this film. Perhaps we can pierce the shield around our collective hard hearts long enough to speak humanely about strangers crossing borders without required papers. At least, speak humanely.

Borders do not seem able to sustain their raison d'être to keep strangers out. It is so last millennium a concept. We see desperate people land on foreign shores and create mountains of life jackets. People slip through border gates, climb over and under fences, burrow underground tunnels. With or without authorization, they will tell you they have good reason to flee their homes, and international law allows for exceptions to border rules. They may not tell you how harsh life is when they succeed, harsh as it was for the first flood of Irish, Italian and Eastern Europeans after their ships sailed past the Statue of Liberty.

Generations moved up through a society excoriating their ancestors for their foreign food, accents, music. Generations became Americanized and cultures absorbed, more like frozen TV dinners than savory melting pots. That experience has proven just as true of Vietnamese, Cambodian and of other Asian, African and Latin American immigrants. Once settled in, we hardly recognize our former foreign selves. That being true, in a lucid moment of the next collective dream, can we uncover a path for new strangers who would be us?

In the following poem, consider the sage who pleaded this cause 50 years ago.

Little Notre Dame - 1966

by Reggie Morrisey

Whirling in her black and white habit,

Sister Anita Marie, O.P.

stood for everything she knew.

Red-faced, ignited,

her fingers clutching chair backs,

she shot data attacks

at have-no-care America and

prophesized near doom,

footnoting a future that loomed

in a small women's college.

Defensive,

doubting her knowledge and

passionate certainty,

we squirmed in desk sets

rented by part-time dollars,

wry eyebrows raised

like flags for veteran fathers

at the Third World riot

conditionally guaranteed

by the white-robed sage

of upward mobility.

"Rising expectations

cannot be hosed,

beaten or ignored.

Acres are torched

as one tyrant

overthrows another.

A solitary soldier

will not stand

between you and

scores of raging

Old World sons.

How can we fight

every fight?

Instead, we’ll watch

the globe burn

on our color sets at night."

Some scoffed at her vision

and laughed in the hall,

dismissing a century's

global brawl.

Inclined to devise

sweet Rockwellian schemes

for manicured lawns and

upper class means.

Wars later, the good sister's

new world turned.

Between the commercials,

her precious globe burned.

Veiled Arabs hurled

not-so-veiled

car-bombing threats.

And Asians lost years, gripping

storm-tossed decks.

Nicaraguan reformers drew

blood and land deeds.

Apartheid purveyors bowed to

equal right creeds.

No continent of color untouched.

And rare the woman of color untouched,

in each village and city depraved.

Still, our Yuppies gained eager maids

that Immigration missed.

Standing on manicured lawns,

they cradled our upward dreams.

A high price mobility means.

Yet in the world class - First to Third,

"Free" is the operative word.

I heard, wise Sister.

I heard.